In this post we meet William Forewell, clergyman of Dundee, as he departs on his voyage, 1876 with his 14-year old son as crew. Their plan is to sail to France and back, which takes them two years. The clergyman had ‘Silver Cloud’ built for him by A. Burn, Montrose to his own specifications, gleaned by comparing local boats. She was half-decked, just 19’ overall with 7’ 9” beam. Sailing south from Broughty Ferry on 18 May, he reflects on the craftsmanship of his helm and anchor, as the tiller splits and the anchor drags. We then read of his passage from St Andrew’s Bay past Bass Rock and through the Farne Islands towards Berwick.

For the first time for seven weeks found the wind blowing from the west, so we let go our mooring off Broughty Ferry at 7 a.m, and bore away with wind and tide. There was a commotion outside, however, which we did not expect, the result of the previous easterly winds, and about eight o’clock, as we left the channel of the Tay, at buoy No. 3, when steering through the swell that rose on the banks, the tiller split in my hand. I had lost the one made with the boat by Mr. Burn; and the person who made this one had not been accustomed to select wood for sea wear. It was cracked all over, I had said as much, but I should have stoutly rejected it, and so I had myself to blame. You must satisfy your own judgment in these things, however much experience the workman may suppose himself to possess. Nothing of more importance on board a ship than the helm and the anchor; nothing is associated with death and life so much as these. The anchor made by the Montrose smith for the ‘Silver Cloud’, I on first sight condemned. It was neither size nor shape. The reply was, ‘I have made anchors for thirty years.’ Still I had my misgivings, secretly ordered another from another smith, and for safety sailed with two.

Among the first days we had a sail on the Tay, we were suddenly caught by a snarling sou’wester, and, going with wind and tide at such a speed, rather than risk catching my moorings when the tug of the buoy might have torn me out of my vessel, mooring the skipper and letting his ship go, as I neared them I flung out the anchor made on the experienced anvil; but we drifted dangerously. Then I addressed the waves, making my voice distinct even amid the roar and rushing of the waters, telling them with all the emphasis I could command that ‘the man that made that anchor had made anchors for thirty years.’ But if ever things inanimate were gifted with the power of speech, it was the waves that day when they broke on the bow of my boat, and distinctiy repeated each time, ‘Bosh! bosh! bosh!’ I cast out the other anchor, and though by this time very near the shore, saved the ship. The tiller was tied with cord, and under a fresh breeze we soon sped across St. Andrew’s Bay, where it became clear that the roof of our little cabin was anything but watertight, when through press of sail or bounding wave our little vessel began to dip her bow in the sparkling brine.

We rounded the North Carr Beacon about ten o’clock. The wind would now have the full fetch of the Forth. My ship was untried in waves like these; neither was my compass tested since I had shipped 30 fathoms of iron chain, to which of necessity it lay very near; and the mist hung upon the sea and hid everything beyond May Island. The compass course to St. Abb’s Head was S. by E . ¼ E., distance 26 miles; but in the circumstances I steered two points to the right of it, keeping the island in sight on my starboard till I saw how my vessel would behave, for possibly I might requir to run back under lee of the ‘East Neuk’. The full force of the fresh westerly breeze issuing from the Firth braced up our nerves; it also cleared the eye. For away over the May Island one piece of mist seemed thicker than the rest, and out of it soon grew the dim outline of the Bass Rock. No more thoughts of shelter; we reasoned we hed felt the full force of the sea; took our departure from the May for St. Abb’s S. by E. ¾ E., 21 ½ miles; big ships came mounting down the Firth; the breeze fair abaft, and the day wore on.

By-and-by the wind decreased, the tidal current was adverse, and it was 5 p.m ’ere we were abreast of St. Abb’s. But now the current turned in our favour, a gentle breeze came off the land, and as we quaffed our warm tea the sun shone out and showed St. Abb’s in all the glory of an evening in the riper end of May. Coldingham Bay was alive with tanned lugsails making for Eyemouth, which harbour we should have entered, especially when among such congenial guides, if we had wished a sleep for the night. But wind and tide thus we could reach Berwick in an hour, 7miles, and Scotland would become a thing of the past. Between Eyemouth and Berwick outside it was like the upheaving of a spacious plain, which sank again and you with it, till it was succeeded by another, each rolling away towards the shore, big with wrath, but silent and with a smooth face as they passed us till they burst against the headlands, and sent, their thunder in the twilight athwart the responsive deep.

I had minutely examined the chart, made sure of the course when taking the harbour, and was abreast of Berwick by 8 p.m, ready to make the attempt. On the right was the stone pier, on the left was a bank on which the rollers wildly broke. There was a fresh in the Tweed caused by the rain; besides the tide was running out, and the amount of wind we had was too light; our progress was therefore slow. The wreck of a steamer lies in the channel, the entrance being to the windward of the wreck. I could not clear the wreck, and resolved on two boatlengths of a tack towards the breakers on the left. I took the helm and the lug, leaving the shifting of the jib sheets to the rest of the crew. These were somewhat entangled, the jib sheets were not shifted in time, and, rather than wreck or run any further risk, I slackened the lug sheet, and with the stream bore away to sea. Berwick in the twilight, for the present, farewell!

Now we had all that makes sailing inconvenient. It was getting dark, it was wet, it was cold, and by midnight it became absolutely calm. It had not been in my purpose to sail that night, and so, further than a general glance I had not examined the chart beyond Berwick, and with the roar upon the dark shore I resolved to keep outside the Farne Islands. Although so many ships have been wrecked among these rocks, some companies having forbidden the inside passage to their steam ships at any time, two steamers in the dark came out from among them and crossed our bow. A lighthouse beam is a gladsome thing as it dances on the waves; but a sleamer’s lights, if you see them all, and especially on a calm night, are like the fierce eyes of a wild beast peering through the dark, possibly on the way to send you all to destruction. Although we were taking the more dignified course, we gave due heed and honour to these dangerous desperadoes. Whenever we sighted a steamer and discovered the course she was steering, although we knew it, we let ‘the rule of the road’ go to the wind, and took the rule of the hare, unless it was dead calm. We threw ourselves on the tack that sent us furthest out of her way, and when her lights disappeared resumed our course.

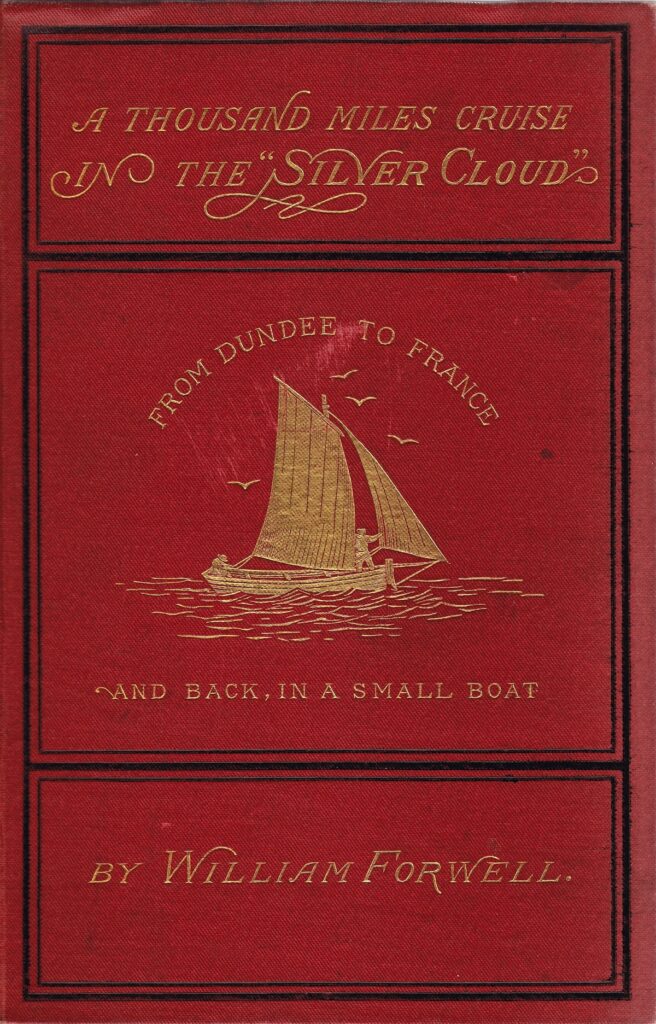

‘A thousand miles cruise in the ‘Silver Cloud’: from Dundee to France and back, in a small boat’ (1878)

William Forewell

You must be logged in to post a comment.