Just 23 miles wide at the narrowest point between Dover and Calais, the English Channel has separated Britain from mainland Europe since pre-historic times. During the last Ice Age, between 6500 and 10000 years ago, the chalk was swept away leaving the famous white cliffs of Dover on the English side of the channel, separating England from our French neighbours. Since the age of the train, we’ve crossed the Channel by steamship, ferry, hovercraft and, since 1994, via the Channel Tunnel. How did we get there before the train?

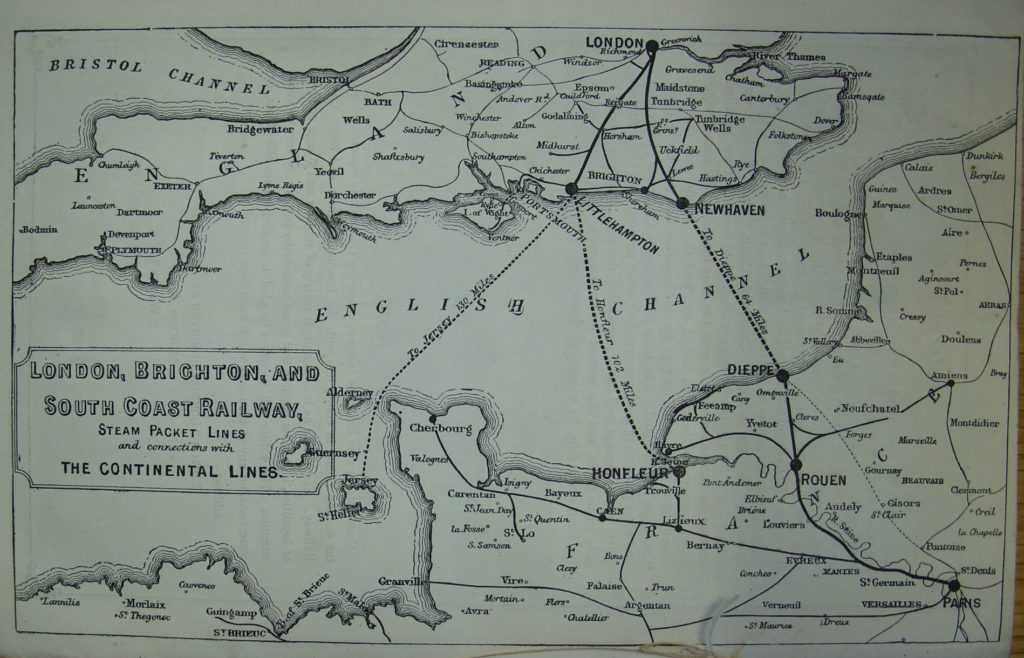

From its early Saxon origins as a fishing community, Brighthelmstone became Brighton and in the 18th century fishing boats, colliers and other cargoes continued to be hauled onto the beach as there was no natural harbour. Before the age of the train, travellers in England had to rely on horse and carriage, with the quickest sailing route to France being from Brighton. Built as a landing stage for the sailing ships, the Royal Suspension Chain Pier was constructed in 1823. Brighton to Dieppe was a busy packet boat service, with up to nine vessels plying the Channel. Several more services became popular and the Brighton landing stage was out of use by the mid 1880s, being destroyed by a storm in 1896.

For over 200 years, engineers have presented plans, proposals and dreams to restore a ‘land bridge’, but they consistently met with political, technological, engineering, geological and economic problems. Completed in 1994, with St Pancras redeveloped in 2007, the tunnel and associated ‘portals’ on the French and English sides of ‘la Manche’, is one of Europe’s biggest infrastructure projects. Today’s travellers from London to Paris depart from the elegance of the restored Victorian gothic St Pancras International and speed through the tunnel to arrive at Gare du Nord in under three hours. That’s just double the time it takes to get to Brighton by train

You must be logged in to post a comment.