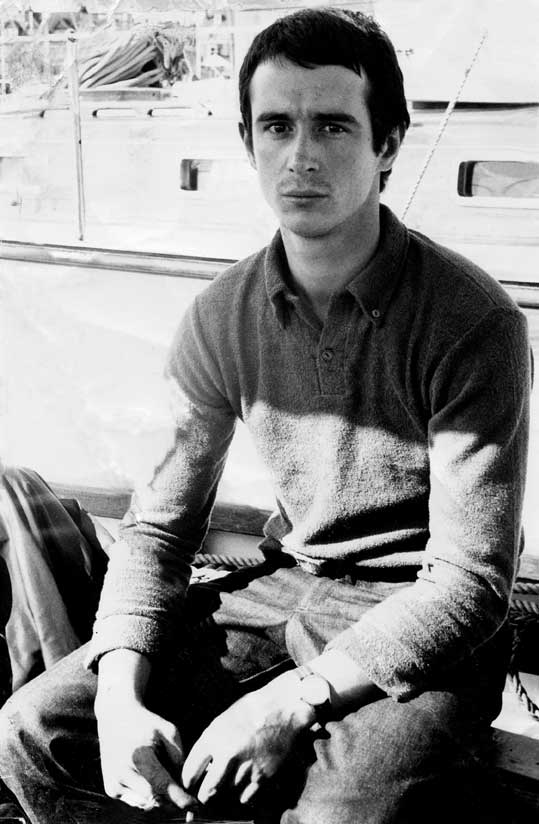

Martin Goodrich recalls a sailing adventure as crew member aboard the Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter ‘Madcap’ whilst he was an art student in August 1967.

My Father rang me to say that Ray, whom I had sailed with on ‘Ianthe 2’, had again invited me to join him on a sailing trip. Ray had chartered a sailing vessel and organised a mixed crew of German and English young people for a three-week sailing adventure to the Channel Islands and north Brittany Coast. I was free so readily agreed. The vessel was ‘Madcap’, a Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter, built by Davies & Plain in Cardiff, 1875. She was 43.2′ length on deck with 12.3′ beam, drawing 7.5′. I joined up and on arrival it was explained that this was a working trip and that a wide number of maintenance tasks would need to be carried out as part of the cruise. Fine, not a problem. The crew was introduced: three English and five German lads, Ray who had chartered the vessel, and his five-year-old daughter. Later that day we were introduced to the owner, Commander John Burfield of Pulborough Sussex. He looked us over, gave out the list of tasks and the order of when and where these were to be carried out. We had two days initial preparation, painting and varnishing, rigging maintenance, and getting to know each other. I became aware that Ray and Commander John were in deep conversation, the outcome of which was that the owner had decided to join us on the trip. I could sense that Ray was not best pleased, and the decision was a bit of a ‘fait accompli’, one that created confusion as to who was the skipper amongst the crew, and an unspoken conflict.

The next day we set off at high tide through what seemed to me to be the complex harbour of the Chichester Channel, and out into Hayling Bay motoring. I asked when would we be putting up the sails: ‘Oh, not today’ said Commander John. Our next heading was Cowes, and it was Cowes Week. Hundreds of boats were evident as we motored to the port, and we were passed by several very large and impressive, posh sailing yachts, over 100′ long, with at least 25 visible crew on deck. They whooshed past, very exciting. We entered the Harbour and were given moorings. I think the Commander must have been well connected as we moored alongside Eric Tabarly’s ‘Pen Duick 2’, a single-handed transatlantic vessel, later he was invited to the Royal Yacht Squadron. There were other famous vessels, but the significance of all of this escaped me as I was just itching to go sailing.

The next day we motored to Poole Harbour. Too short a distance for sailing I was told. Here we calibrated the fuel and water tanks by pouring in gallon after gallon and marking it on the glass tube gauge set in the side of the cockpit. This took all day. Other tasks were hoisting the sails, checking rigging, rehearsing the various roles while sailing, where different ropes, warps, sheets are kept. Then we were briefed on the next day’s passage. The plan was to sail to the North Brittany coast, leaving with the tide in the early morning, sailing through the day and the night, expecting to make landfall before midday. We were then organised into pairs for two-hour watches. Night sailing was a first for me so I was full of expectation and excitement. We motored out of Poole Harbour into the bay where we made ready, set the sails and headed south in force 3 winds from the west. We were set fair just off the wind, on a single tack for the crossing. I was on watch with Ray 0200-0400 hrs and I was able to renew our old comradeship from our voyage together in ‘Ianthe 2’ the previous year.

I took in all he had to offer about sailing at night. Simple things: if those ship lights stay in the same position relative to ourselves, then we are on a collision course; if the lights change, then the ship is either going behind us or across our bows; ‘But which?’ was the question I was asked. I probed Ray on the addition of the Commander to our trip but Ray gave nothing away. Soon we were off watch and the beginnings of dawn became evident along with the outline of the French Coast. We went to our bunks but I was too excited to sleep. As dawn broke we could see the coast, sightings were taken to fix our position and to decide which port we should make for. Lezardrieux was the nearest. Things came to a head between our two skippers as we approached the entrance of the Riviere de Trieux for Lezardrieux. There was a violent disagreement as to the correct approach for entry, something about the set of the tide and there we’re close to the rocks, as they wrestled with the tiller! I have to say that given they were both experienced Captains, this was very surprising to me. As an art student with very little sailing experience, such conflict seemed to me to be the nature of life and par for the course, but was it mutiny?

It was settled with some degree of humiliation for the Commander, who had to give way. Once we had got to port Ray decided to do the honourable thing and leave the ship with his young daughter while asking all his friends to stay with the Commander for the return to Chichester.

That evening the Commander, John asked all the crew to join him at his expense for a restaurant meal. Everyone but me politely declined. I decided to go along not out of solidarity, nor to get to the bottom of this man, but for a good meal, and splendid it was too. The Commander did however rather patronise me, calling me his cockney sparrow. I got my first real taste of the officer class and the class differences between us.

On the walk back a speeding car passed us just as we entered the village and port. As we walked up onto the quay looking for our tender, we could see a vehicle submerged in water besides the quay; the lights were still on and the driver struggling to get out. I jumped in and managed to free the door, releasing a very grateful, drunken Frenchman as the car’s lights faded. He had driven straight off the road and into the slipway, my third rescue. It’s a good feeling to have rescued, and I myself was rescued some years later in Dutch waters, very drunk. I reflected after this event that notions of class superiority are pretty irrelevant.

Next morning the Commander told the story of the rescue to the crew in an attempt to boost morale and comradeship, which it did. We set to, to do more maintenance and passage planning to Guernsey’s St Peters Port. The next day we left. The weather had changed to wind S/W 5/6, we reefed down with jib and mainsail set; a fantastic trip engrossed by the power of sailing and the handling of the vessel in heavy seas; great fun sliding down the wave troughs. We arrived safely in St Peters Port and the rest of the day was ours, so to the pub with the crew to gossip about our Commander. The next day we sailed to Cherbourg. The wind had dropped; we set full sail and I really enjoyed helming. Then into port, and after we had taken on fuel, we moored alongside on the pontoons. We were given the afternoon off, but I volunteered to stay aboard and keep watch. After an hour I saw a young lady sailing around in a small, clinker-built, varnished dingy. I hailed her and asked if I could join her. She agreed. She spoke good English and we had a great afternoon with me learning how to sail a dinghy, as this was my first time. She was surprised: ‘But you came in a big sailing vessel!’ The next day we moved to a harbour wall so that when the tide had dropped we could scrub the bottom, repaint and anti-foul it over two days.

As a reward for successfully completing this, the Commander took us all to a restaurant for a meal. I came with my new French girlfriend; everyone was impressed. Soon it was time to sail back to England. We left the Harbour under motor and no attempt was made to set sails. I asked why as the winds were light S/W on the perfect beam. The Commander replied that he and most of the crew wanted to get back as soon as possible and a sailing passage would be too slow. I protested: ‘What’s wrong with night sailing?’ I had signed up for three weeks of work and sailing experience, not motoring and we were going back early. I felt cheated and spent the day snoozing in the forward hatch in protest.

Irony of ironies, as soon as we passed by Sandown Bay the command came to hoist sails and we progressed up the river to Chichester with topsail and all, ‘Not too short a distance for sailing’, I quipped. I felt sure that this was a performance of swank to impress onlookers more than to appease my desire to sail rather than motor. All in all a great adventure not to have been missed, and certainly a great influence on me.

Martin Goodrich, East Coast Area member of the OGA

You must be logged in to post a comment.