In this extract, W M Nixon recalls a special global circumnavigation by Tim Magennis, President of the Dublin Bay OGA in their 50th anniversary year. Setting out from Durban, South Africa, in 1965 they took two years to circle the globe in the 47ft ‘Sandefjord’, a classic Colin Archer ketch built in 1913 and celebrating her 100th anniversary with a passage back to Norway.

It was the morning of Sunday 21 February 1965 when the 47ft ‘Sandefjord’ slipped her lines from a quayside packed with friends and well-wishers in Durban, South Africa, and headed seaward down the harbour with an accompanying fleet. Instantly into open ocean at the pierheads, she was soon heading west for Cape Town, reeling off the miles on a close reach as her goodwill flotilla peeled off one by one to head back to the shelter of the great port. But they were to be out there again in increased numbers two years later to greet her when she returned from the eastward, with 30,729 miles completed in a classic global circumnavigation which had gone on from Cape Town through the South Atlantic to the Caribbean, thence to the Panama Canal and on to the Galapagos, then on across the wide blue waters of the Pacific to Polynesia and eventually to Sydney in Australia. From there it was northwards, cruising through the Great Barrier Reef and on into the Indian Ocean, then southwestward on the final long transoceanic leg, back to a rapturous welcome in Durban.

It is Tim Magennis, longtime member of the Dublin Bay OGA, who gives us the direct link to this fine voyage. With a boyhood in the coastal village of Ardglass in County Down, most of his early seagoing experience was with summer jaunts on one of the local fishing boats. But having shown a youthful a talent for journalism, he went straight into it from school, soon finding his way to national newspapers in Dublin. From there, Tim went on to work in newspapers in Africa in the late 1950s, and by the early 1960s found himself on the staff of the largest daily in Durban. Always drawn to the sea, he was fascinated by Durban’s port, the largest in South Africa. Yet despite its size he noted that his paper gave port matters no prominence whatever. When he pointed this out to the editor, he was promptly detailed off to write a regular column about maritime affairs. Hanging out on the waterfront became part of his job. Through this, he met up with the people restoring ‘Sandefjord’. She was a classic Colin Archer Redningskoite, one of the last of the type to be built specifically for rescue work, Number 28 constructed in 1913 by Jens Olson with Risor Batbyggeri. Although motor-powered lifeboats had been about since G L Watson pioneered the first one for the RNLI in 1904, sail and oar continued to pay a prominent role in many rescue services, and the exclusively sail-powered ‘Sandefjord’ accompanied the Norwegian fishing fleet from 1913 to 1934.

Stood down from rescue duties after 21 years of gallant service, in 1935 she was bought by noted Norwegian ocean voyager Erling Tambs, who wanted to provide a Norwegian presence in the forthcoming Transatlantic Race from Newport, RI to Bergen. Crossing the Atlantic westward in May 1935, ‘Sandefjord’ was pitch-poled with the loss of one crewmember. But Tambs and his remaining shipmates still managed to nurse her to Newport where they sorted the damage, and then raced back across the Atlantic. In 1939, with World War II imminent, Tambs sailed her out to South Africa, where she was sold to Tilly Penso of the Royal Cape YC, who kept her with loving care for twenty years. She became a cherished part of the Cape Town sailing scene, with her rig simplified for family sailing by conversion to Bermudan ketch. With Tilly Penso’s death in 1959, she was sold by his estate, and went through a quick succession of owners. Though her gaff rig was restored, she was slowly going downhill, and by 1962 was more or less abandoned in Durban. There, already on the slide to becoming a rotting hulk, she was spotted by a restless young South African of Irish descent, Patrick Cullen (23), who despite having a very young family, had notions of a seagoing adventure. His brother Barry (24) was a qualified master mariner, and the two of them saw the potential in ‘Sandefjord’.

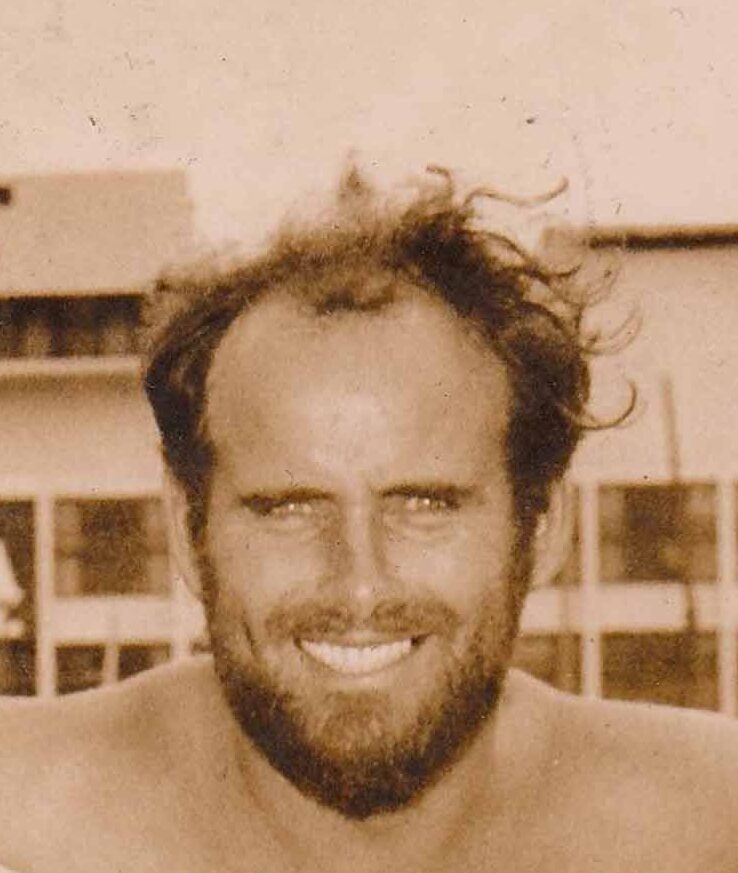

The notion of a two year voyage round the world to the romantic South Seas took shape, with a proper film of it to make their fortunes afterwards. They managed to buy ‘Sandefjord’ with the support of their mother in 1963, and secured a place on the Durban waterfront for a restoration project which soon became almost a re-build. But these were two very determined young men, and soon they were attracting like-minded spirits to join their project. It was all done in a very businesslike way, with crewmembers being required to sign a clearcut contract and commit one thousand rands up front to the voyage. It was in these heady days of hard work and boundless horizons that the recently-appointed Durban maritime correspondent met up with them. At 32, Tim Magennis may have been a few years older than the next oldest member of the ‘Sandefjord’ crew, but he always seemed much younger than his years – he still does at 81 – and within days he was being swept up with shared enthusiasm. He jacked in his dream job, though agreeing to file reports from around the world and write up the story for the paper on their return, and signed on as the final member of the Sandfjord’ crew of six, throwing himself into the final frantic months of preparing the ship for the great voyage.

It was a classic cruise, all the better for being at a time before sailing became overly regulated and monitored. Thus although they’d a painfully slow passage from Panama out to the Galapagos, at one stage taking an entire week to make good one hundred miles, once they got to those extraordinary islands they were able to cruise among them with a freedom denied in today’s heavily regulated environmental protection of that unique place. Tahiti was still a place of romance before mass tourism made it blasé, and among the Pacific islands Tim’s talents with the guitar were much in demand. But they surely paid for their lotus eating in the South Seas. The passage on to Sydney, far from being tradewind bliss in southeasterlies, became a slog almost all the way against unseasonal headwinds which culminated in yet another gale on the final night at sea, bringing down the mizzen around their ears, with a fierce struggle to secure the broken spar on deck.

But when they finally arrived exhausted and battered at the Cruising Yacht of Australia in Rushcutters Bay, they’d come to the right place. After taking 50 days for a passage which should have taken only about 33, with stores down to just 20 cans of baked beans, they were distinctly peckish. However, lunch on arrival at the CYCA was just the job with enormous steaks. Tim is slim now, as he was then. Yet like the rest of the crew, having enjoyed one enormous Australian lunch, he simply sat on and ate his way right through a second one, with all the trimmings. They gave a boat a complete refit at Sydney, glued and fastened the saved mizzen mast, and then headed on north for the Great Barrier reef. But inevitably at this final stage of the voyage, resources were becoming stretched, so when the gearbox on their Perkins diesel gave up the ghost, they sold the otherwise sound engine for 400 Australian dollars at Thursday Island and completed the rest of the voyage, along the north coast of Australia, across the Indian Ocean and home, under sail only.

Their average speed for the entire cruise was 4.18 knots, but when you see the one hour and 54 minute film – which has recently been re-mastered and is well worth viewing for this glimpse of life when the world was a simpler place – you soon realize that with half a decent breeze, the handsome ‘Sandefjord’ could trot along in some style. And for her young crew, it was simply the time of their lives. Back in Durban, reality intervened. Tim found himself locked into a hotel room until he completed the account of the voyage for his newspaper. Then a message from home from an older brother, an officer in the Irish army, was a three line whip – he was to get back to Ireland soonest for their parents’ Golden Wedding anniversary. He returned to an Ireland considerably changed. In the late 1960s, the place was finding new and much-needed vitality. He never returned to Durban, but married Ann and settled in Dun Laoghaire on the shores of Dublin Bay, perfectly fitting his new job as PR for the Irish Tourist Board. He became a voice for Ireland. You could always be sure that the usually gruff William Hardcastle of the BBC’s World at One would have a smile in his voice after chatting on the air with Tim Magennis about something of interest in Ireland.

As for ‘Sandefjord’, Patrick Cullen sailed her with his family in the Cape Town to Rio Race of 1971, and then cruised north through the Caribbean to New York and on to Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, where she was based from 1972 to 1976. She was sold there by Patrick and Barry in 1976 to Erling Brunborg, who sailed her home to Norway. Brunborg, a stalwart of the Colin Archer world, eventually sold her in 1983 to Petter Omtvedt, who in turn spent ten years on a massive re-build, making her exactly as she’d been as a Redningskoite. When this was completed, she was bought in 1993 by Gunn von Trepka who – with her husband Alan Baker – has completed many Tall Ship Races in European waters as family sailing ventures. And as this year is her Centenary, there’ll be a mighty party in Risor at the end of August which hopefully will be attended by all the surviving members of the ‘Sandefjord’ crew – sadly, Pat Cullen, who had the first spark of the idea of the world voyage, died some years ago.

Needless to say, Tim Magennis will be in the heart of the Centenary party, the father of the crew. But meanwhile, he has much to attend to in Dublin. With retirement he has been able to focus even more strongly on his love of sailing and maritime heritage, and it was very right with the world when he was acclaimed as the new President of the Dublin Branch OGA in the Autumn of 2012, no better man with the Golden Jubilee Cruise arriving at the end of May. His own boat these days is the 23ft ‘Marguerite’, a lovely little clipper-bowed gaff sloop designed in 1896 by Herbert Boyd, who later designed the Howth 17s in 1898. A great friend and fellow owner of another vintage Boyd boat is Patrick Cullen’s son Sean, who is very much an Irish seafarer these days – he commands one of the national maritime survey vessels, a long way indeed from racing aboard ‘Sandefjord’ from Cape Town to Rio as a very young seafarer in 1971.

Tim’s seagoing interests are many. He sailed many miles offshore with Don Street of Glandore in southwest Ireland, aboard Don’s famous ‘Iolaire’. And more recently, while sailing across the Bay of Biscay aboard the square rigger ‘Jeanie Johnston’ on a pilgrimage with a difference to Santiago de Compostela, his mobile phone rang, and the connection lasted just long enough to tell him he’d become a grandfather for the first time. That’s the way it is with Tim Magennis. There’s always something new on the horizon. And there’s quite a past too, for this is a man who once upon a time sailed right round the world on a fine gaff ketch when all the world was young, and everything was possible.

Contributed by W M Nixon, sailing correspondent for Afloat.ie

You must be logged in to post a comment.